In 1741, four African slaves lived in the colony for every 1.2 free white. This imbalanced population combined with high mortality, the threat of conflict with Native Americans, shortages of food and goods, and isolation produced a colony in which African, French, and Spanish cultures blended to create a unique culture known as Creole. Because most of the Africans who first arrived in Louisiana were of one nation, the Bambara, they succeeded in preserving their language and culture and, through their solidarity, ultimately acted as an Africanizing influence on Louisiana. European colonists, aware of their precarious position in the colony, were inclined to work together with slaves and afford them some rights under the Code Noir.

While the system was certainly brutal for African slaves, the harsh conditions of life in Louisiana resulted in difficulties for all settlers. Since many of the colonists were themselves rejected by French society and forced into exile in Louisiana as criminals or debtors, historian Gwendolyn Midlo Hall states, “Africans arrived in an extremely fluid society where a socio-racial hierarchy was ill defined and hard to enforce.” Hall expertly sums up the situation in colonial Louisiana, “Desperation transcended race and even, to some extent, status, leading to cooperation among diverse peoples.” Though the arrival of Anglo-Americans with the Louisiana Purchase resulted in stricter laws governing slavery and narrower views in terms of race, Louisiana society would remain more diverse, fluid, and racially ambiguous than the other Southern slave states.

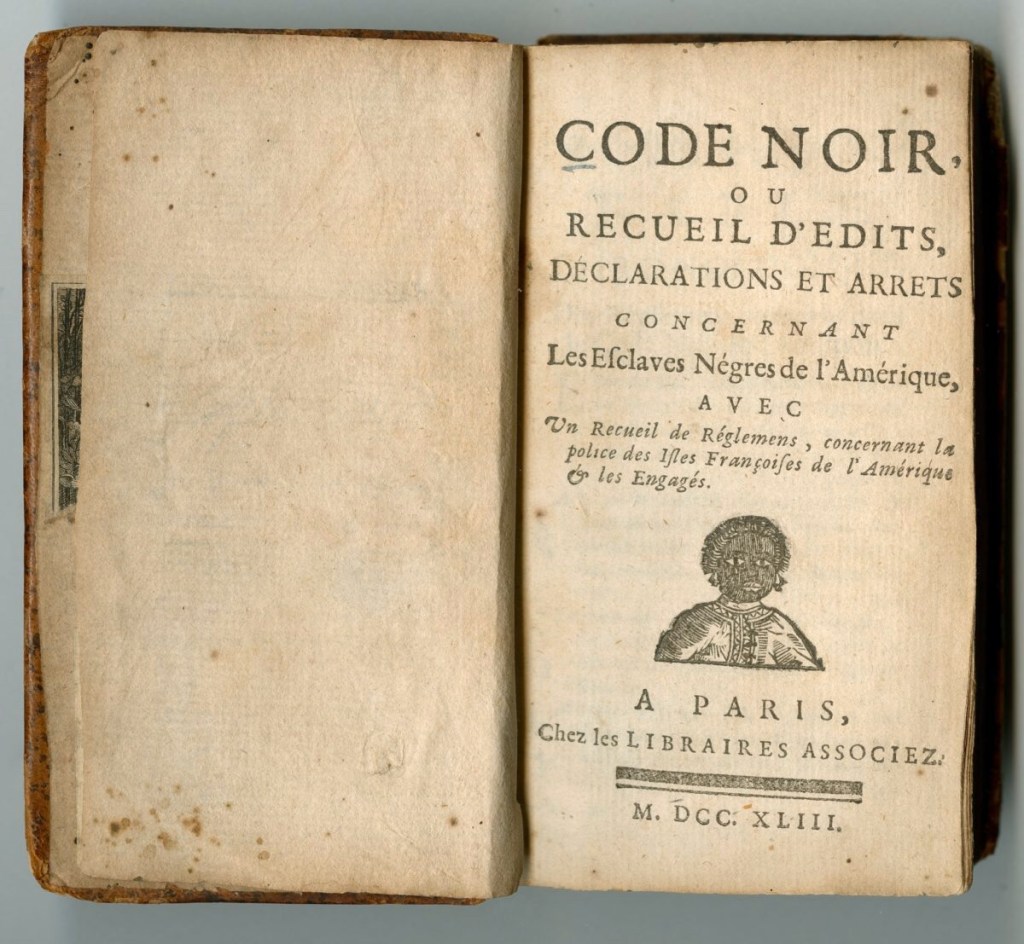

The Code Noir was established in 1724 to regulate slavery in colonial Louisiana. The Code Noir stated that slaves were to be instructed in the Catholic faith, given food and clothing allowances, and allowed to rest on Sundays and the right to petition a public prosecutor if they were mistreated. Also, young children had to be sold with their mothers. The Code Noir prohibited slaves from owning property or testify against whites.