“Like the measles, which are so delightful in retrospect because we remember only the period of convalescence and its accompanying chicken and jellies, Bohemia seems to be a state which grows dearer the farther away you get from it.

The only trouble with this pitiless exposé of Bohemia is that I know practically nothing about the subject at all. I have only taken the most superficial glances into New York’s Bohemia and for all I know it may be one of the most delightful and beneficial existences imaginable. It merely seemed to me like a good thing to write about, because the editor might, while reading it, think of a dashing illustration that could be made for it.

And, if I have been entirely in error in my estimate of Bohemia, maybe some real, genuine Bohemian will conduct me, some night, where the lights and good-fellowship are mellow and rich and where we may sit about a table and sing songs of Youth and Freedom, and Love, and Girls, like so many Francois Villons.”

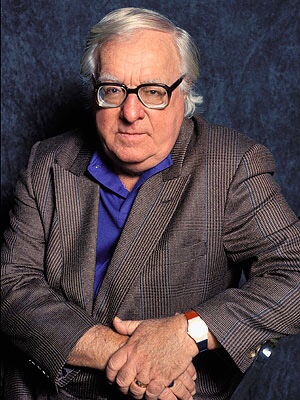

~ Robert Benchley, 1919 from “Vanity Fair Magazine: The Art of Being a Bohemian.”

Pictured Above: Cartoon of Robert Benchley and Dorothy Parker.