“I shall dance all my life. . . . would like to die, breathless,

spent, at the end of a dance.”

~ Josephine Baker, 1927

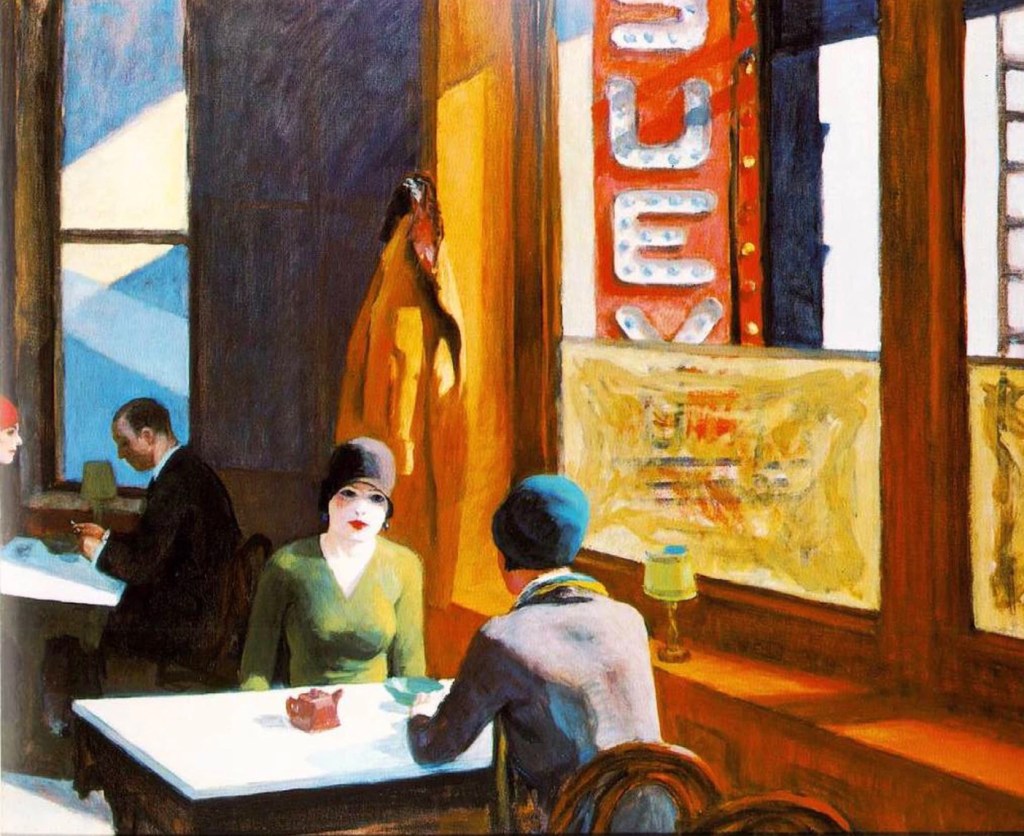

An international star of the Jazz Age, known for her daring dances, exotic costumes, and menagerie of pets, Josephine Baker was born into poverty in St. Louis in 1906. A natural comedian with dreams of performing on stage, she talked her way into her first dance role as a determined young teen and then jumped at the opportunity to travel with a vaudeville troupe. It didn’t take long for her natural talent to shine on stage, and she made her mark as “the funny one.” Josephine exploited her dancing and performance skills, doggedly pursuing her dream of becoming a respected star. By the time she was 19, Josephine was performing in Paris, and a whole new world opened up. In a few short years she had propelled herself from a St. Louis girl with a dream to a full-fledged Parisian sensation.

Outside being a famous entertainer her sense of commitment to fighting racism and injustice grew and matured as she traveled around the world, leading her to become an outspoken participant in the US Civil Rights Movement, conduct important espionage work for the French Resistance during World War II, and adopt her “rainbow tribe”— 12 children, each from a different nationality, ethnicity, or religious group—in an effort to prove racial harmony was possible.

Baker was celebrated by artists and intellectuals of the era, who variously dubbed her the “Black Venus”, the “Black Pearl”, the “Bronze Venus”, and the “Creole Goddess”. Born in St. Louis, Missouri, she renounced her U.S. citizenship and became a French national after her marriage to French industrialist Jean Lion in 1937. She raised her children in France.

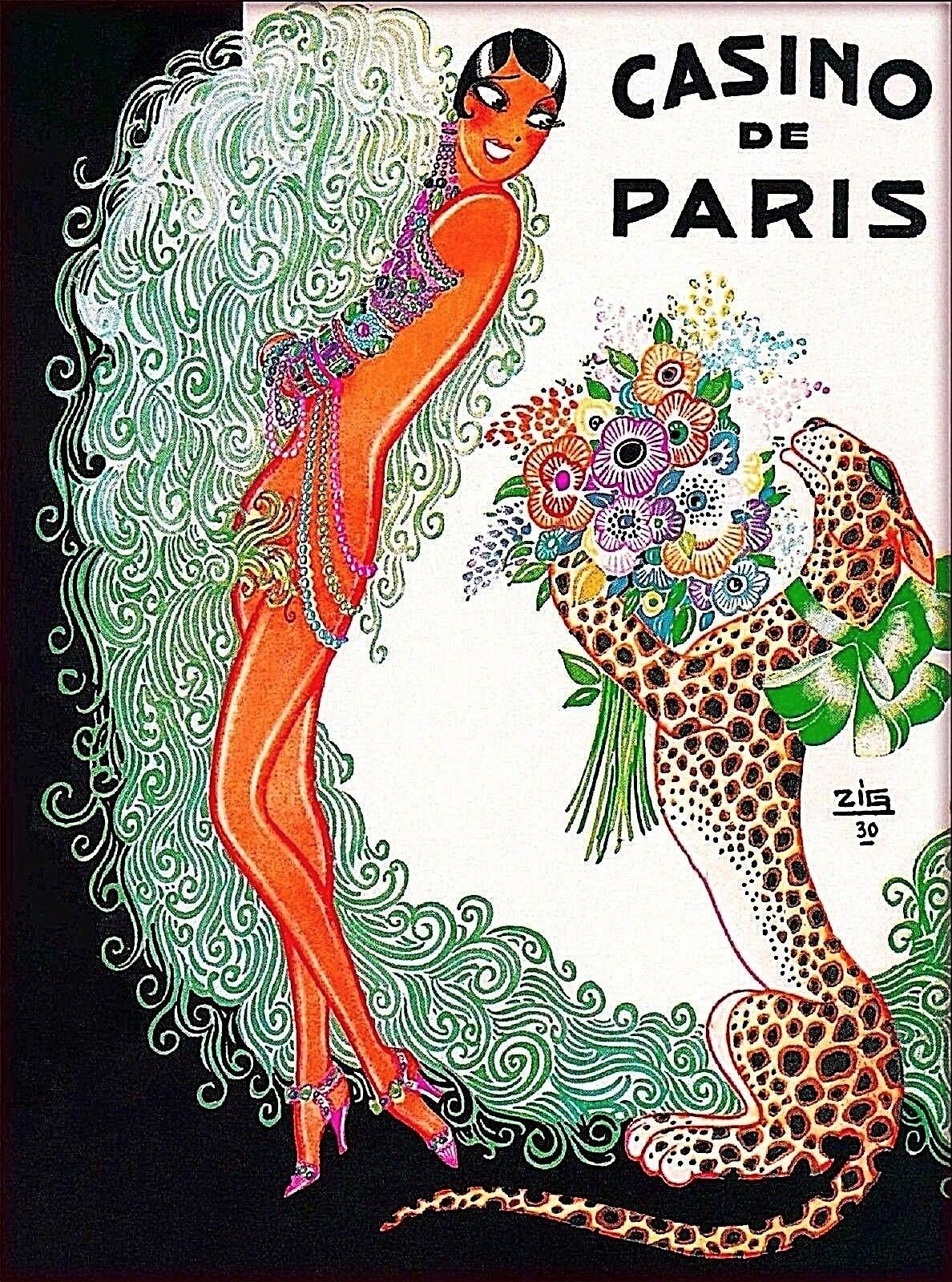

n Paris, she became an instant success for her erotic dancing, and for appearing practically nude onstage. After a successful tour of Europe, she broke her contract and returned to France in 1926 to star at the Folies Bergère, setting the standard for her future acts.

Baker performed the “Danse Sauvage” wearing a costume consisting of a skirt made of a string of artificial bananas. Her success coincided (1925) with the Exposition des Arts Décoratifs, which gave birth to the term “Art Deco”, and also with a renewal of interest in non-Western forms of art, including African. Baker represented one aspect of this fashion. In later shows in Paris, she was often accompanied on stage by her pet cheetah “Chiquita,” who was adorned with a diamond collar. The cheetah frequently escaped into the orchestra pit, where it terrorized the musicians, adding another element of excitement to the show.

She aided the French Resistance during World War II. After the war, she was awarded the Resistance Medal by the French Committee of National Liberation, the Croix de Guerre by the French military, and was named a Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur by General Charles de Gaulle. Baker sang: “I have two loves, my country and Paris.”

Baker refused to perform for segregated audiences in the United States and is noted for her contributions to the civil rights movement. In 1968, she was offered unofficial leadership in the movement in the United States by Coretta Scott King, following Martin Luther King Jr.‘s assassination. After thinking it over, Baker declined the offer out of concern for the welfare of her children.

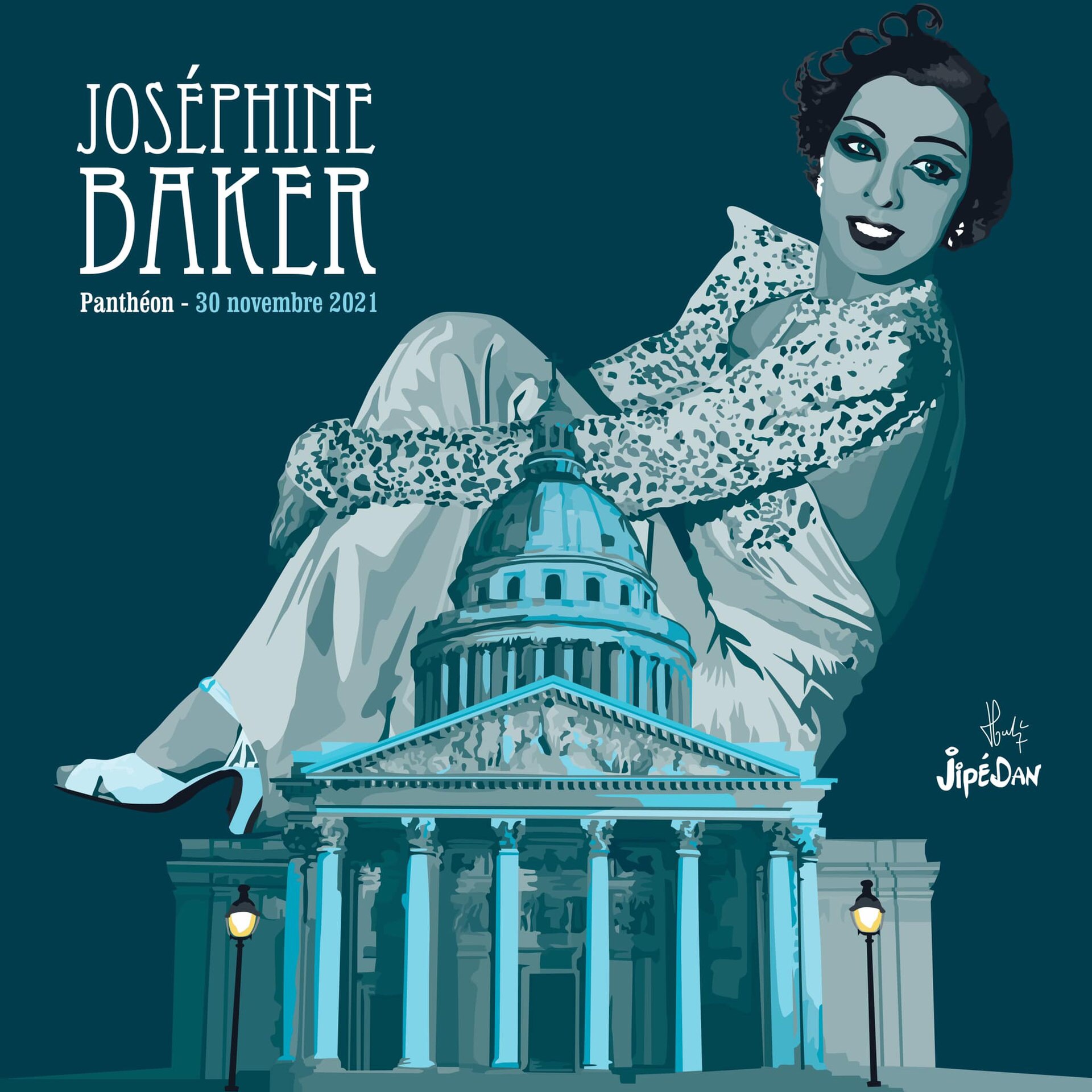

On 30 November 2021, she entered the Pantheon in Paris, the first black woman to receive one of the highest honors in France. As her resting place is to remain in Monaco a cenotaph will be installed in vault 13 of the crypt in the Panthéon

Sources: Peggy Caravantes