The Shtriga was a vampire-like witch that was found in Albania. The creature was similar to the Strigon, which was a witch found among the southern Slavs, the strigoi of Romania, and the vjeshtitza of Montenegro.

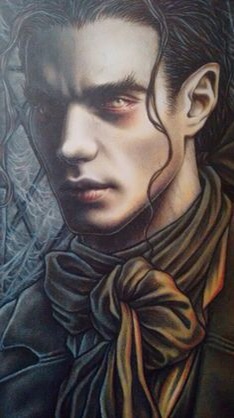

The Shtriga usually took the form of a woman who lived undetected in the community. She was difficult to identify, although a sure sign was a young girl’s hair turning white.

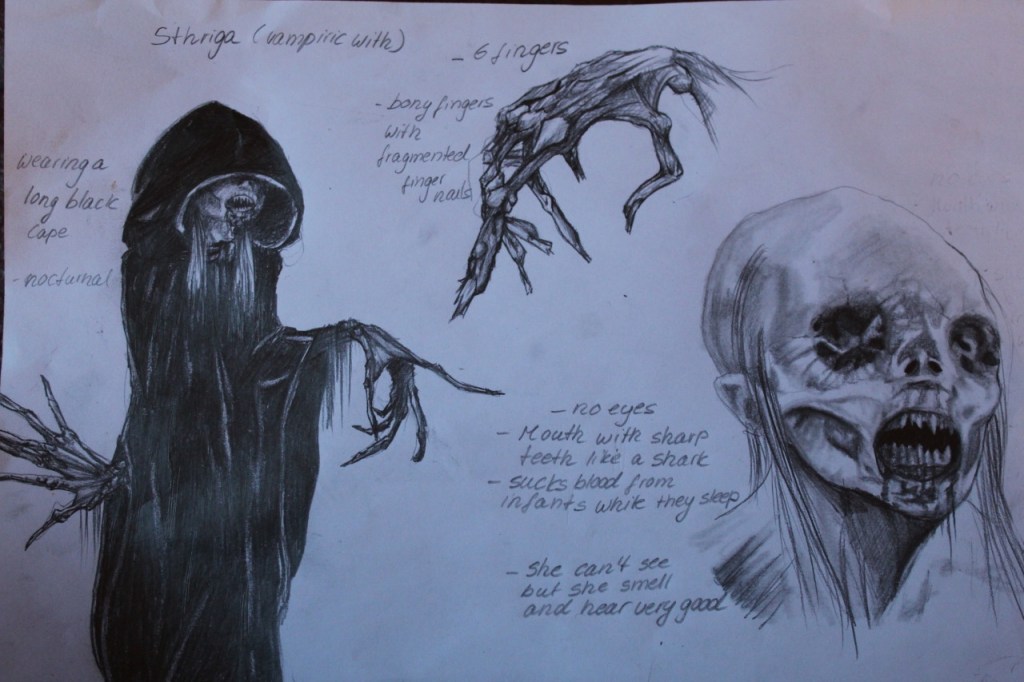

The vampire witch attacked her prey at night, usually in the form of an animal, such as a moth, fly, or bee.

In order to catch a Shtriga, two methods can be attempted:

~ On a day when the community gathered in the church, a cross made of pig bones could be fastened to the doors. Any Shtriga inside would be trapped and unable to pass the barrier.

~ If one followed a suspected Shtriga at night, one could see her vomit blood at some point after she sucked the blood of her victims. The vomited blood could be bottled and turned into an amulet to ward against witches.

Legend of the Shtriga:

According to legend, only the shtriga herself could cure those she had drained (often by spitting in their mouths), and those who were not cured inevitably sickened and died.

The name can be used to express that a person is evil. According to Northern Albanian folklore, a woman is not born a witch; she becomes one, often because she is childless or made evil by envy. A strong belief in God could make people immune to a witch as He would protect them.

Usually, shtriga were described as old or middle-aged women with grey, pale green, or pale blue eyes (called white eyes or pale eyes) and a crooked nose. Their stare would make people uncomfortable, and people were supposed to avoid looking them directly in the eyes because they have the evil eye. To ward off a witch, people could take a pinch of salt in their fingers and touch their (closed) eyes, mouth, heart and the opposite part of the heart and the pit of the stomach and then throw the salt in direct flames saying “syt i dalçin syt i plaçin” or just whisper 3–6 times “syt i dalçin syt i plaçin” or “plast syri keq.”

In some regions of Albania, people have used garlic to send away the evil eye or they have placed a puppet in a house being built to catch the evil. Newborns, children or beautiful girls have been said to catch the evil eye more easily, so in some Albanian regions when meeting such a person, especially a newborn, for the first time, people might say “masha’allah” and touch the child’s nose to show their benevolence and so that the evil eye would not catch the child.

Edith Durham recorded several methods traditionally considered effective for defending oneself from shtriga. A cross made of pig bone could be placed at the entrance of a church on Easter Sunday, rendering any shtriga inside unable to leave. They could then be captured and killed at the threshold as they vainly attempted to pass. She further recorded the story that after draining blood from a victim, the shtriga would generally go off into the woods and regurgitate it. If a silver coin were to be soaked in that blood and wrapped in cloth, it would become an amulet offering permanent protection from any shtriga.

In Catholic legend, it is said that shtriga can be destroyed using holy water with a cross in it, and in Islamic myth it is said that shtriga can be sent away or killed by reciting verses from the Qur’an, specifically Ayatul Kursi 225 sura Al-Baqara, and spitting water on the shtriga.