The federal government had a number of forts and military installation in the South. As Southern states seceded, many of them were quickly turned over by state forces. One of the major exceptions was the federal facilities in and around Charleston.

Federal troops there were concentrated in Fort Moultrie. In the middle of Charleston harbor sat Fort Sumter, unoccupied and still under construction. On November 15th Major Robert Anderson was named commander of Federal troops in Charleston. He quickly came to the conclusion that Fort Moultrie was not defensible. The unoccupied Fort Sumter was defensible as it was situated in the middle of the harbor surrounding by deep water.

On the night of December 26th Major Anderson, mustered his command and moved in the stealth of night to Fort Sumter. The Southerner felt betrayed. They believed that they had an understanding with Anderson to maintain the status quo.

When Lincoln took office the issue of Ft Sumter arose and he was forced to come to grips with the problem. On one hand reinforcing the fort seemed increasingly difficult. Lincoln was afraid of using force, since this might sway those Southern states such as Virginia that had not yet seceded to secede. On the other hand Major Anderson was becoming a hero in the North.

Finally after receiving varied advise from his advisors Lincoln decided to resupply the fort.

The Confederate government under Davis felt that they could not allow the fort to be resupplied, and Davis despite opposition from the Confederate Secretary of State Robert Toombs – he stated “Mr. president at this time it is suicide, murder, and will lose every friend at the North. You will wantonly strike a hornets nest which extends from mountains to ocean, and legions now quiet will swarm our and sting us to death. It is unnecessary; it put us in the wrong it is fatal.”

On the afternoon of April 11th, General Beaulegrad issued a formal demand of surrender to Major Anderson. When major Anderson received it he refused it, however he stated to the Confederate representatives, that if they had only waited another few day the fort would be forced to surrender, as it would be without food. Colonel Chesnut one of the Confederate representatives asked if he could include that in his report. Anderson assented.

Beauregard then asked for direction from President Davis. Davis agreed to call off the bombardment if he could get a firm commitment as to the time of the surrender from Anderson. At midnight on the 12th Confederate representatives again demanded the surrender of the garrison. Anderson answered that they would surrender by the 15th, but with an important proviso, that only if the fort was not resupplied. This was not considered a sufficient answer for the Confederates. As the confederates began to leave, Anderson stated” If we never meet in this world again, God grant that we may meet in the next.”

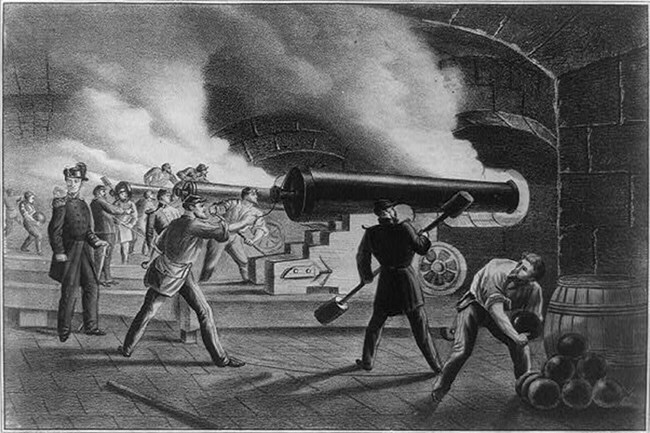

Thus at 4:30 AM confederate batteries began their bombardment of Fort Sumter. The confederate bombing was effective, and included a floating battery, in a makeshift boat. Anderson’s counter fire was limited by the his lack of munitions and by his limited number of soldiers. Finally 34 hours after the bombardment began, Anderson surrendered.

Reaction:

Sumter had fallen- now it was Lincoln’s turn to respond. He did so by a call for troops: Lincoln stated, “Now I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, in virtue of the power in me vested by the constitution, and the laws, have thought fit to call forth, and hereby do call forth, the militia of several States of the Union, to aggregate number of seventy thousand.

The nation responded by a series of meetings in every part of the North. Thousands came forth with enthusiasm. A New York mother of five sons who enlisted stated:” I was startled by the news referring to our boys, and, for the moment felt as if a ball had pierced my own heart. For the first time I was obliged to look things full in the face. But although I have always loved my children with a love that none but a mother can know, yet when I look upon the state of my country, I cannot withhold them; and in the name of their god and their mothers god, and their country’s god I bid them to go. If I had ten sons instead of five I would give them all sooner than have our country rent in fragments.”

While the call for militia succeeded in raising an army, it was the final blow in the attempts to keep the Virginia and other wavering states in the Union. The Border states and the states of the Upper South all responded with words similar to those of Kentucky: “Kentucky will furnish no troops for the wicked purpose of subduing her sister southern states.”

Virginia was the first Southern state to secede, and with her the man who was to become the South leading General – Robert E. Lee. Lee was a reluctant sessionist, he had stated two months earlier “I fear the liberties of our country will in the tomb of the great nation. If Virginia stands by the old Union so will I. But if she secedes ( though I do not believe in secession as a constitutional right, nor that there is sufficient cause for revolution) then I will sill follow my native State with my sword, and if need be, with my life.”

Next Arkansas joined the confederacy, they were followed in May by North Carolina and Tennessee.

Immediately following the riots secessionists in Baltimore destroyed the railroads bridges and the telegraph lines thus cutting off Washington. For days Washington was cut off, with no additional replacement troops coming. Panic reined in Washington- Lincoln looked out the White House windows wondering when reinforcements would show. Finally in April 25th the 8th Mass Infantry and the 7th New York Regiment, landed at Annapolis Maryland. The New York Regiment managed to repair a branch line of the B&O that had been sabotaged and soon they arrived in the capital, whose citizens breathed a collective sigh of relief.