One of the most recognizable ancient Egyptian symbols, the ankh, is one of the few vestiges to survive the decay of the old religions and still be in use today.

What Is the Ankh?

The ankh is an ancient Egyptian hieroglyph or symbol known as the cross of life or key of life and dates back to the Early Dynastic period (3150 BC – 2613 BC). The symbol resembles a cross with a loop on the top. The ankh is seen in the hands of almost every deity, carried by the loop or with arms crossed and one in each hand. The symbol was found as far afield as Persia and Mesopotamia in dig sites and was said to connote both mortal existence as well as eternal life.

Origin

Various theories exist about the origin of the symbol, but popular opinion suggests the origin is unknown. In 1869, mythologist Thomas Inman believed the ankh was a sexual symbol, and Egyptologist E. A. Wallis Budge similarly thought it may symbolize the belt buckle of Isis or Tyet. The ceremonial girdle or Knot of Isis, was alleged to represent female genitalia and fertility. Egyptologist Alan Gardiner posited it represented a sandal strap, as the word sandal and ankh came from the same root word. His theory was further affirmed by the fact that the sandal was a part of daily life in Egypt and the ankh also represented life. In a more recent publication, The Quick and the Dead, the authors claim the ankh ties to ancient cattle culture.

Usage

The symbol was portrayed on amulets, with the Djed (meaning stability) or Was (meaning strength) – symbols which were said to provide the protection of the gods to the wearer. Ptah is also seen making offerings with these three symbols in images representing him. The ankh was associated with the purifying power of water. This was evident on numerous temples where the king was depicted with two gods pouring a stream of ankhs over his head to cleanse him.

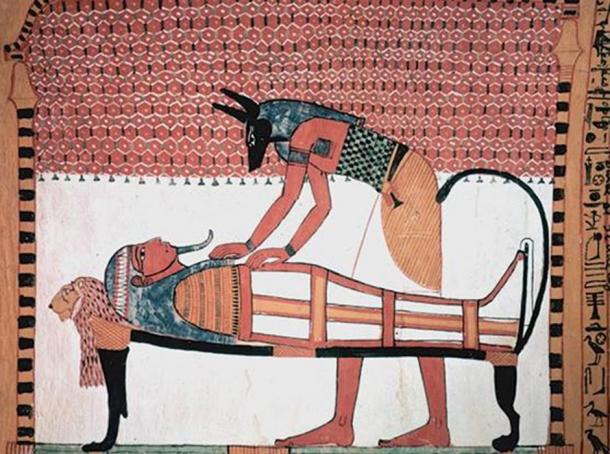

Gods and kings are frequently depicted holding the ankh to show their immortality and command over life and death. For those that had passed into the afterlife, the symbol was carried when their souls were weighed or aboard the boat of the Sun God, indicating their desire for immortality like the gods. According to the Dictionary of Symbols by Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrant, it also represents the spring of eternal life and divine virtues. When it was held by the loop, usually in funeral rites, it may have been perceived as the key to opening the gateway to the Fields of Aalu, the Egyptian version of the Elysium Fields. Chevalier and Gheerbrant further postulated that when the ankh was placed between the eyes, it symbolized the duty of the person to keep the mystery he was initiated into a secret.

Early Dynastic and Old Kingdom Period

In the Early Dynastic period, the symbol became popular through the rise of the cult of Isis and Osiris. Isis is seen holding the ankh more frequently than other deities. Since the cult of Isis promised immortality through personal resurrection, the symbol became imbued with greater meaning and potency.

During the Old Kingdom Period, the ankh was well known as a symbol of eternal life. The dead were called ankhu and the symbol appeared frequently on sarcophagi and caskets.

Middle Kingdom and New Kingdom Period

The word ’nkh became associated with mirrors, from the Middle Kingdom Period onward. The Egyptians believed mirrors were magical and used them in divination. An ankh-shaped gilded mirror was found in Tutankhamun’s tomb. The Egyptians believed the afterlife was a perfect reflection of life on earth – a mirror image. During a particular festival, called the Festival of Lanterns, the Egyptians would light oil lamps to create a night sky of stars on earth to mirror the stars in the sky and the afterlife. When they did this, it was said to help them commune with the dead who had passed on the Fields of Aalu or Field of Reeds.

During the New Kingdom, the ankh was used in ceremonies and became associated with the cult of Amun. During the Amarna period, images of Aten the sun-disk often contained ankhs at the end of the sun’s rays.

Knot of Isis

The Tyet, or Knot of Isis, is very similar to the ankh. The arms of the cross are bent downward, differentiating the Knot of Isis from its counterpart, but it similarly means life or welfare. Sources claim the Tyet combines the concept of life and immortality with the knots which fasten mortal life to earth. To savor immortal life, the knot purportedly needs to be unraveled.

Modern Use

The symbol is used by modern Pagans as a symbol of faith, in healing and to promote psychic communication. It is viewed as a symbol of life by various new age religions. Thelemites, followers of the religion created by Aleister Crowley, also make use of the ankh as a union of opposites, a symbol of advancing one’s destiny or of divinity.