The night attendant, a B.U. sophomore,

rouses from the mare’s-nest of his drowsy head

propped on The Meaning of Meaning.

He catwalks down our corridor.

Azure day

makes my agonized blue window bleaker.

Crows maunder on the petrified fairway.

Absence! My hearts grows tense

as though a harpoon were sparring for the kill.

(This is the house for the “mentally ill.”)

What use is my sense of humour?

I grin at Stanley, now sunk in his sixties,

once a Harvard all-American fullback,

(if such were possible!)

still hoarding the build of a boy in his twenties,

as he soaks, a ramrod

with a muscle of a seal

in his long tub,

vaguely urinous from the Victorian plumbing.

A kingly granite profile in a crimson gold-cap,

worn all day, all night,

he thinks only of his figure,

of slimming on sherbert and ginger ale–

more cut off from words than a seal.

This is the way day breaks in Bowditch Hall at McLean’s;

the hooded night lights bring out “Bobbie,”

Porcellian ’29,

a replica of Louis XVI

without the wig–

redolent and roly-poly as a sperm whale,

as he swashbuckles about in his birthday suit

and horses at chairs.

These victorious figures of bravado ossified young.

In between the limits of day,

hours and hours go by under the crew haircuts

and slightly too little nonsensical bachelor twinkle

of the Roman Catholic attendants.

(There are no Mayflower

screwballs in the Catholic Church.)

After a hearty New England breakfast,

I weigh two hundred pounds

this morning. Cock of the walk,

I strut in my turtle-necked French sailor’s jersey

before the metal shaving mirrors,

and see the shaky future grow familiar

in the pinched, indigenous faces

of these thoroughbred mental cases,

twice my age and half my weight.

We are all old-timers,

each of us holds a locked razor.

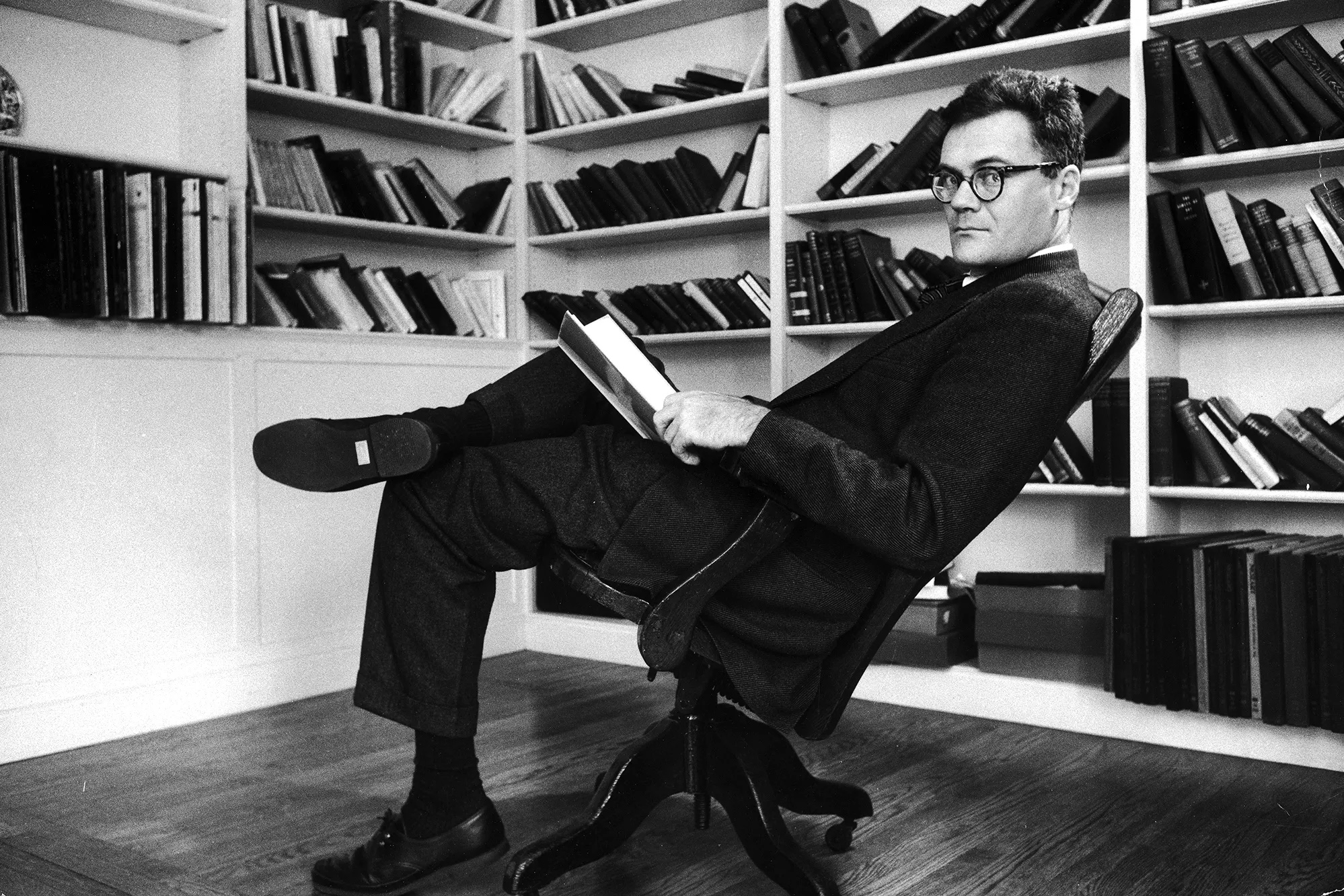

~ Robert Lowell, from Life Studies, 1959