The seelie and unseelie courts of Scottish fairies are a particular feature of the folklore of that country; the clear separation of the faes into good and bad groupings that’s entailed is almost unique in folklore. Moreover, the notion of the two courts has, in recent years, attracted considerable attention and popularity- notwithstanding the fact that they are not mentioned in the majority of the Scottish faery-lore texts and collections. Probably the majority of recorded Scottish folklore relates to the Highlands and Islands, the Gaelic (and Norse) speaking regions, which may explain why we have relatively little material documenting the two courts.

The Scots word ‘seelie’ derives from the Anglo-Saxon (ge)sælig/ sællic meaning ‘happy’ or ‘prosperous.’ The evolution of the word in Middle English and Scots seems to have been in two directions. One sense was ‘pious,’ ‘worthy,’ ‘auspicious’ or ‘blessed.’ The second development extended the meaning incrementally through ‘lucky,’ ‘cheerful,’ ‘innocent,’ and ‘simple,’ from whence it was a short final step to ‘simple-minded,’ as the modern English ‘silly’ denotes. Because of this evolution, as well as because of the dialectical differences between English and Scots, it is preferable to use ‘seelie’ rather than to try to translate it. In passing, we might observe that Scots is in many cases far nearer to original Anglo-Saxon than modern English, which has imported so many French and Latin words.

By late medieval and early modern times, ‘seelie’ or ‘seely’ in Scots meant happy or peaceable, as in ‘seely wights,’ and the ‘seely court,’ which was the ‘happy or pleasant court.’ It followed from this that ‘unseelie’ or ‘unsilly’ described something that was unhappy or wretched. The poet Dunbar referred to Satan’s “unsall meyne” (his “wretched troop of followers”), a phrase which could be a very appropriate term for the fairies.

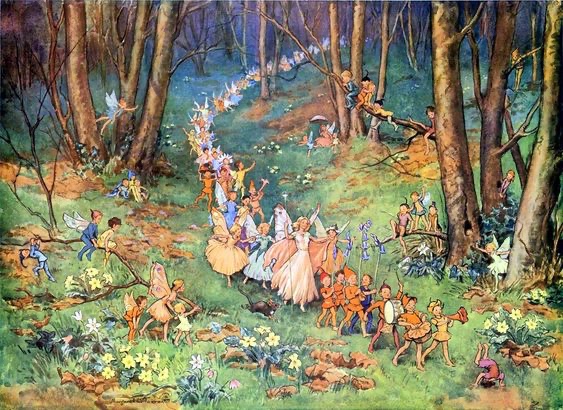

The Scots word with a variety of spellings, particularly sely, and meanings including “lucky, happy, blessed”; the adjective is applied euphemistically to fairies in Scotland. This term is used in relation to the Scottish fairies, calling them both ‘Seelie court’ and ‘gude wichts’. Court in this sense meaning a group or company, and wichts meaning beings. Seelie fairies are those who are benevolently inclined towards humans and likely to help around homes and farms. It should be remembered though that they are as able and likely to cause harm as any fairy. The use of the term Seelie in relation to fairies dates back to at least the 15th century in Scotland and can be found in a book from 1801; in the ‘Legend of the Bishop of St Androis’ it says:

“Ane Carling of the Quene of Phareis

that ewill win gair to elphyne careis;

Through all Braid Albane scho hes bene

On horsbak on Hallow ewin;

and ay in seiking certayne nyghtis

As scho sayis, with sur sillie wychtis.”

“One woman of the Queen of Fairies

that ill gotten goods to Elphin carries

through all broad Scotland she has been

on horseback on Halloween

and always in seeking certain nights

as she says, with our Seelie wights.”