Date: 1440 BC

Discovered: Elephantine, Egypt

Period: Exodus

Torah Passages: Exodus 2:11–5:1; 12:37-41; 14:4-30; Acts 7:20-30

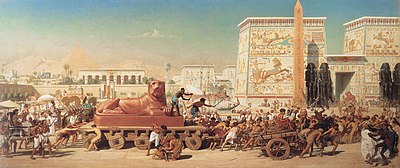

Pharaoh and his servants had a change of heart toward the people… So he made his chariot ready and took his people with him… and he chased after the sons of Israel (Exodus 14:5-8).

Pharaoh Amenhotep II reigned over Egypt beginning in about 1450 BC during the powerful 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom. His monuments and inscriptions indicate that he was one of the most boastful pharaohs of ancient Egypt, claiming such feats as being able to shoot arrows through a copper target a palm thick, rowing a ship by himself faster and farther than 200 Egyptian sailors, singlehandedly killing 7 prince warriors of Kadesh, having the kings of Babylon, the Hittites, and Mitanni all come to pay tribute to him, and supposedly conducting the largest slave raid in Egyptian history.

According to a match of chronological information from Egyptian king lists and the Bible, Amenhotep II was probably also the pharaoh of the Exodus, which occurred in approximately 1446 BC. One of the most significant artifacts relating to the circumstantial evidence for Amenhotep II being the pharaoh of the Exodus is a stele that he commissioned to commemorate one of his campaigns.

While earlier in the 18th Dynasty the Egyptians had a powerful military, especially during the reign of Thutmose III, who conducted 17 known military campaigns, after the beginning of the reign of Amenhotep II there is a steep decline. In fact, Amenhotep II had only two confirmed campaigns during his reign—the first took place prior to the Exodus, while the second was primarily a slave raid that occurred soon after the Exodus and was recorded on the Elephantine Stele.

This monumental stone inscription with its accompanying artwork was originally erected at the southern city of Elephantine, and it records the campaign of Amenhotep II to Canaan in which he claims to have brought back over 101,128 captives to be used as slaves.31 In comparison, other Egyptian military campaigns of the period brought back nowhere near the amount of captives, with the largest total being only 5,903, and as a result most scholars consider the number of slaves captured by Amenhotep II in this text to be a massive exaggeration. Because this happened right after the Exodus, perhaps it is indicative of an urgent need to replace the lost slave population in Egypt, or purely as propaganda making it appear that the pharaoh had recovered or replenished the slaves lost during the Hebrew Exodus.

Additional indicators include that the pharaoh preceding the Exodus must have had a reign of over 40 years, since Moses killed an Egyptian and fled to Midian for 40 years until the pharaoh who knew him had died. Thutmose III, the father and predecessor of Amenhotep II, reigned for 54 years and is the only pharaoh in the dynasty with a reign of 40 or more years. The Exodus pharaoh must also have recently begun his reign, since Moses returned and confronted the Exodus pharaoh soon after the previous pharaoh died, and Amenhotep II took the throne only about four years or less prior to the Exodus.

The first campaign of Amenhotep II was launched in his third year, or approximately 1448 BC. The second campaign, to Canaan, occurred in his seventh year, approximately 1444 BC, which seems to have been only one or two years after the Exodus.

Sources: Essential Judaism, Unearthing the Bible, myjewishlearning.com, Chabad.org