“Grits is the first truly American food. On a day in the spring of 1607 when sea-weary members of the London Company came ashore at Jamestown, Va., they were greeted by a band of friendly Indians offering bowls of a steaming hot substance consisting of softened maize seasoned with salt and some kind of animal fat, probably bear grease. The welcomers called it “rockahominie.”

The settlers liked it so much they adopted it as part of their own diet. They anglicized the name to “hominy” and set about devising a milling process by which the large corn grains could be ground into smaller particles without losing any nutriments. The experiment was a success, and grits became a gastronomic mainstay of the South and symbol of Southern culinary pride.”

~ Turner Catledge, New York Times on 31 January 1982

What exactly are Grits?

“Grits are—or is, as the case may be— a by-product of corn kernels. Dried, hulled corn kernels are commonly called hominy; grits are made of finely ground hominy. Whole-grain grits may also be produced from hard corn kernels that are coarsely ground and bolted (sifted) to remove the hulls.

Thus, throughout its history, and in pre-Columbian times as well, the South has relished grits and made them a symbol of its diet, its customs, its humor, and its good-spirited hospitality. From Captain John Smith to General Andrew Jackson to President Jimmy Carter, southerners rich and poor, young and old, black and white have eaten grits regularly. So common has the food been that it has been called a universal staple, a household companion, even an institution.

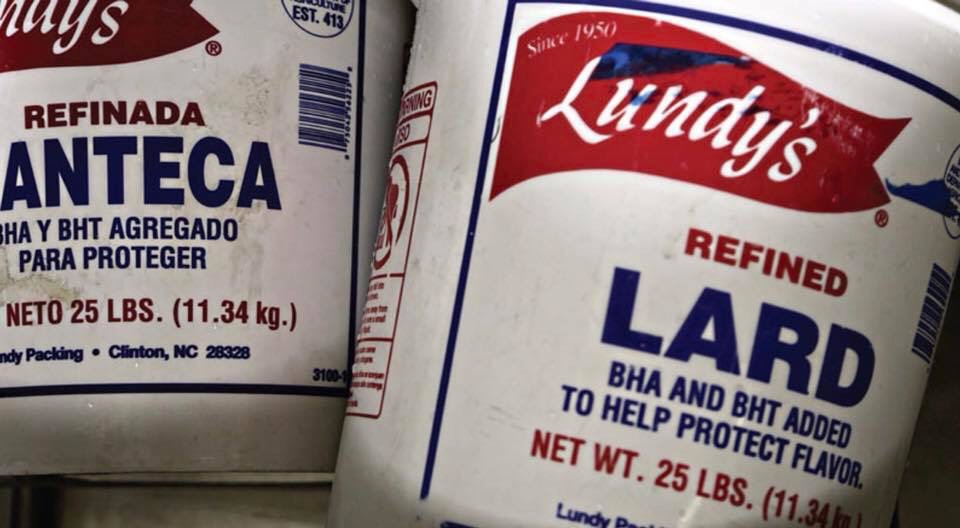

Grits cooked into a thick porridge are so common in some parts of the South that they are routinely served for breakfast, whether asked for or not. They are often flavored with butter or gravy, served with sausage or ham, accompanied by bacon and eggs, baked with cheese, or sliced cold and fried in bacon grease. Mississippi-born Craig Claiborne, the late New York Times food writer, loved grits and published elegant recipes for their preparation.

The last 30 years have seen renewed interest in grits. It has become a part of southern creative expression, as when bluesman Little Milton says, “If grits ain’t groceries / Eggs ain’t poultry / And Mona Lisa was a man.” Jimmy Carter’s presidency in the 1970s led to media interest in grits as a southern icon and the film My Cousin Vinny included a humorous scene of a couple from the Bronx eating the mysterious (to them) grit. By the mid-1980s a new generation of renowned southern chefs, including Bill Neal from North Carolina and Frank Stitt from Alabama, began serving sophisticated dishes with grits, such as Stitt’s grits soufflé with fresh thyme and country ham. South Carolina cookbook author John Martin Taylor helped popularize stone-ground grits, and smaller producers of artisanal grits grew into successful businesses, including Old Mill of Guilford (North Carolina), Falls Mill (Tennessee), Logan Turnpike Mill (Georgia), Adam’s Mill (Alabama), Anson Mills (South Carolina), and War Eagle Mill (Arkansas).”

~ John Egerton, Excerpt From “The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture”